Imagine a group of people living on a dust planet called Gliese 559c. They refuse to farm even walk, because they don't want to disturb whatever lives under and on the ground. Some people run metal hooks through their backs and drag themselves forward. Some pierce their cheeks and tongues with sharp spears to show loyalty. Some even whip their own backs until the skin splits open, saying that once a god "comes into them," they don't feel pain anymore. We cannot quite understand this. But yet they're living, breathing people just like us—and every bit of that suffering is something they choose.

Introduction

All over the world, there are devout religious believers, held tightly by a conviction. Religion isn’t just one thing—it ranges from Christianity and Islam to secretive groups, and sometimes outright cults. And they don’t just differ on details. They argue over the biggest questions there are: What counts as a human being? Why are we here? Even “looking for truth through faith” can mean totally different things to different religions, and people fight over that too.

Even when there is evidence that doesn’t match what they believe, a lot of believers still don’t change their minds. I think they usually fall into two groups. Raised believers are people who grew up in religious families, or who have been educated by religious for years from youth. For them, faith is the lens they use to make sense of everything, so they tend to avoid ideas that might shake it. And for many of them, they simply aren’t able to step back and question their own faith. Converts are people who turn to religion after a long stretch of hardship. They go there for comfort, and they try not to doubt. Doubt pulls them right back toward the fear they’re trying to escape. So when someone challenges their faith, the first thing you may see is anger—but most of the time, it’s anxiety underneath.

There are also people who use religion simply to steady themselves: leaving ordinary life behind to live in the mountains, joining a religion even when their family strongly objects, or disappearing into the wilderness when life feels unbearable. But what is it, really, that keeps their faith standing? Did they actually receive some kind of message from a god?

Raised believers

How belief forms in childhood

For Raised believers, faith often feels like it has been there from the start. For kids who come into contact with religion before puberty, the way their minds work—still not fully developed—can shape belief in a huge way.

In Piaget’s “preoperational stage” (roughly ages 2–7), kids think in a concrete, self-centered way. Instead of having an abstract idea like “all-knowing,” kids may imagine God as a powerful “old man” up in the clouds. That kind of picture can make them feel comfortable. It makes the world safer, and makes a child feel less lonely. If God can see their pain and step in with miracles, the terrible moment doesn’t feel like the end of the story. And if God is “always there,” loneliness doesn’t feel as intense.

Children often hold on to faith for three main reasons. One is that they trust the adults around them, so what parents and religious leaders say can sound simply true. Another is belonging. Religious life usually comes with a community, and being part of it can feel warm and steady—something close to what Maslow meant by the need for love and belonging. Over time, kids start linking “my religion” with those good feelings and shared routines. The third is emotional comfort. Religion gives simple answers to scary questions—like “good people go to heaven”—and that kind of answer can calm childhood fear and draw them into belief.

Rebuilding values as an adult

Children often take religious stories as literal truth. But as they reach adolescence, that starts to change. They get better at thinking for themselves, and the push to be independent can make doubt show up. Suffering makes it even harder to keep everything neat. For example, if a devoted child dies in an earthquake inside a church, believers may question why didn’t God step in if God is there.

After that, people usually go one of three ways. Some come out with a more “grown-up” faith. They learn to live with the contradictions and feel even more convinced. Some rethink their faith. They may start to doubt parts of it, but they still believe there’s something beyond the natural world. And some leave faith behind entirely, going through a major shift in values and rejecting religion altogether.

The suffering that doubts bring

For those who stay religious in the end, the hardest part is finding a solid reason to stand on. The system of “heaven and hell” can sound logically neat—reward and punishment, cause and effect—but in reality, believers are often left with only scripture and what preachers tell them. There isn’t any clear, concrete evidence that can fully back it up.

Trying to “prove God” with reason often backfires. Once you start arguing for something, you’re already admitting it might not be true. And there’s another problem. Religions also contradict each other. That can leave believers with a lingering worry. What if I chose the wrong path and spent my life chasing the wrong truth? Living with that uncertainty, and still staying faithful needs real courage.

The pressure inside

For many believers, the hardest fight is with their own thoughts. If God is all-powerful, then God isn’t fooled by outward devotion. A prayer said with resentment wouldn’t count as real faith. So the most devout believers can feel like they have to hand over their private inner world, and live as if every thought needs to match the doctrine.

This clashes with Descartes’ idea of “I think, therefore I am.” Our thoughts shape who we are, but believers may feel forced to make every thought “correct,” until they start losing their sense of self. Secular people can cry, complain, talk things out, and release pressure. But a believer might fear that showing “weakness” will bring judgment, so they keep swallowing it down—until stress and guilt pile up in a loop.

It’s like a company where the boss and the employee share the same brain. They all want the company to do well, but their interests still different. They are trapped between personal needs and religious duty, with nowhere to retreat and no one to lean on. That kind of inner pain may be more torturing than suffering in the outside world.

Converts

How converts build their faith

Converts often come to religion after a long time feeling lost. Modern people always asking themselves what all the rushing is even for. For certain people, religion provides the ultimate meaning of life and fills the emptiness. Others are drawn to its community, where they no longer fear facing the world alone. That kind of acceptance can ease the pain of being misunderstood for years on end. Still others find a place to anchor their hearts through its concrete daily practices. Believers shift their focus away from the emptiness to tangible actions, avoiding being lost in mental internal friction. People turn to religion for all sorts of reasons, yet countless find something within religious life, or in the values it imparts, that simply feels like a natural fit.

The difficulties Converts face

The pull of secular life

The first test for converts is dealing with everyday temptation. They’ve already lived a normal secular life, so strict rules and a quieter routine can start to feel flat. It’s hard not to compare a night out or a holiday trip with the repetition of prayer and reading scripture.

Part of that pull is just how our brains work. Social media apps are designed to keep us continuous checking—new posts, random little surprises—so we keep reaching for the next bit of excitement. Practices like prayer or meditation don’t work that way. They take patience, and the “reward” is quieter, something you feel slowly rather than all at once.

And people are different by nature. Some get bored of endless short videos after a while—their brains stop reacting as strongly. For them, religious rituals can bring a different kind of satisfaction. Daily prayer, for example, sets small, reachable goals. Meeting those goals can create a safe sense of achievement. Following strict rules can feel like winning a quiet battle, producing a calm, lasting pride—almost like the “runner’s high” after a long run.

Over time, staying away from constant stimulation can make the brain more sensitive to the peaceful reward that faith offers. But not everyone can make that shift. It may depend on the brain you were born with. Some people naturally resist temptation more easily and can stick to religious life. Others have to fight much harder.

The test of time

Holding faith for a lifetime is much harder than converting at the start. Being devout isn’t a short project. For most religions, it means following strict rules day after day until death. Faith isn’t a hobby, and there’s no “weekend off.” For many believers, it becomes their whole life.

At the start, everything can feel intense and new. The rituals feel meaningful, and the commitment gives people a burst of energy—like they’ve finally found a direction. But as the days stack up, those same rituals turn into routine. The newness fades, the emotional “lift” doesn’t come as easily/ Repetition starts to make people down. After that, strict rules can feel less like guidance and more like a burden, even resentment.

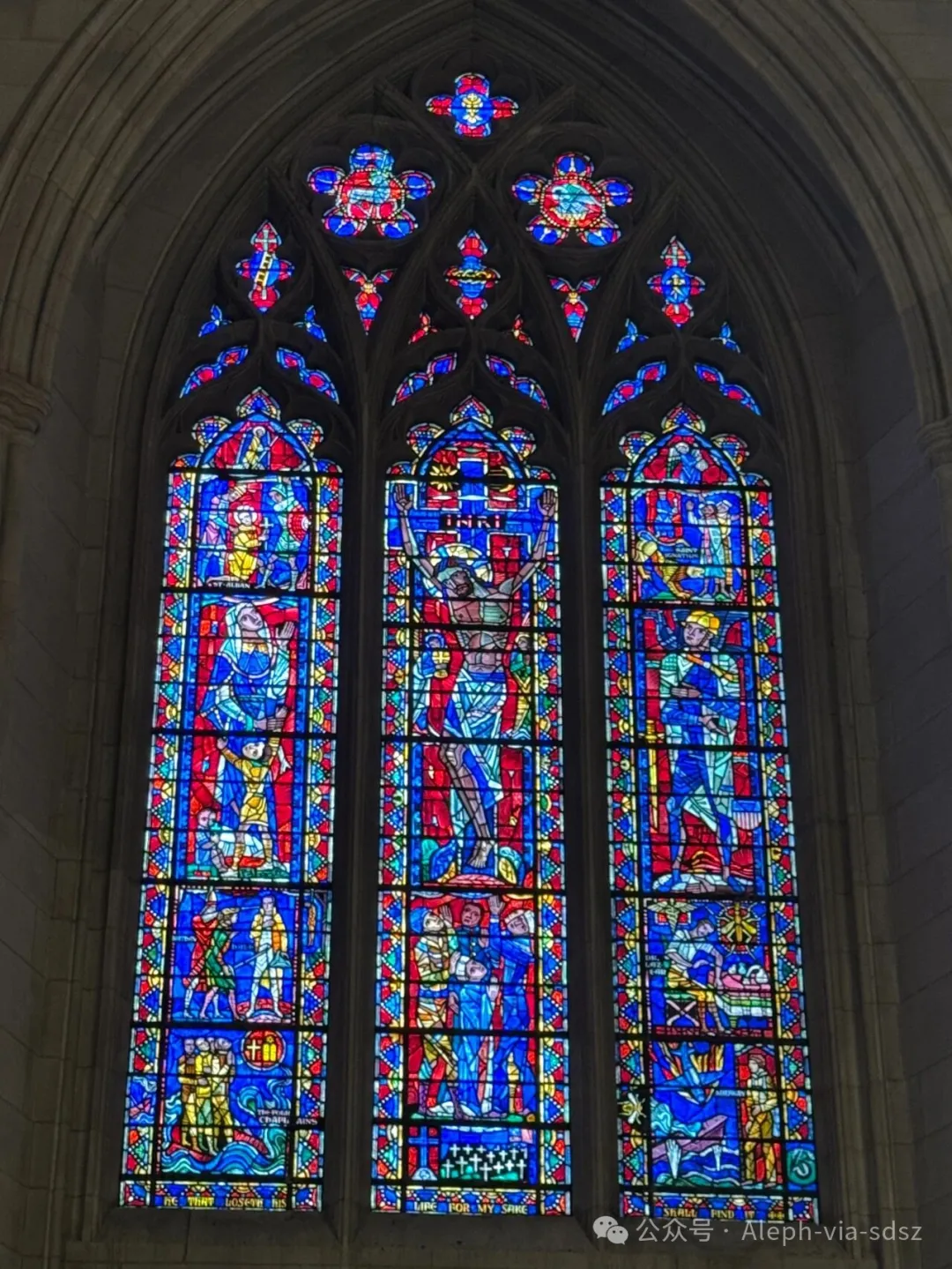

To keep going, believers look for small moments of beauty inside religious life: group chanting or singing, quiet reflection in a beautiful church or temple. Those moments strengthen the feeling of belonging, and that can be what keeps them moving. But again, it differs from person to person. The core issue is still the brain. People who can feel satisfied with small, steady rewards are more likely to find a home in religious routine and keep going. People who need constant change and excitement usually have a harder time with how repetitive religious life can be. Some people can keep doing difficult things even when they’re boring. Others eventually give up and chase faster pleasures instead.

A lifetime of devotion has never been only a test of willpower—it’s the result of determination mixed with the way your brain is built. For most people, staying devout with no guilt and no doubt is destined to be a hard climb.

Conclusion

Religion is a profound subject. This essay isn’t about religion’s grand social role. Instead, I want to look at a quieter side of it, the costs that the most devout believers rarely said out: The constant suppression of doubt, having to keep the own thoughts within what doctrine allows, and a lifelong struggle against the secular world they once left behind.

Many faiths ask believers to be absolutely certain, but they don’t offer concrete evidence in return for that certainty. People who hold on to belief usually do so not because their ideas are airtight, but because faith gives them something to lean on. And honestly, that is profoundly sad.

In the end, the core of faith may not be about God’s truth at all. It may be about how much human beings are willing to sacrifice just to feel that they belong.

Reference

- Maslow's hierarchy of needs https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow%27s_hierarchy_of_needs

- Zhu, Z. X. (Ed.), & Zhu, B. (Rev.). (2019). Child psychology (6th ed., in Chinese). Higher Education Press.

- Piaget’s theory of cognitive development https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piaget%27s_theory_of_cognitive_development

- Dopamine: reward prediction error https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dopamine

- Reinforcement: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinforcement

- Cogito: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogito,_ergo_sum

- Belief_preseverance https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belief_perseverance

- Cognitive dissonance https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_dissonance

- MENG Xianghan, LI Qiang, ZHOU Yanbang, WANG Jin. (2021). Controversies in terror management theory research and its implications for research on the psychology of death. Advances in Psychological Science, 29(3), 492-504.